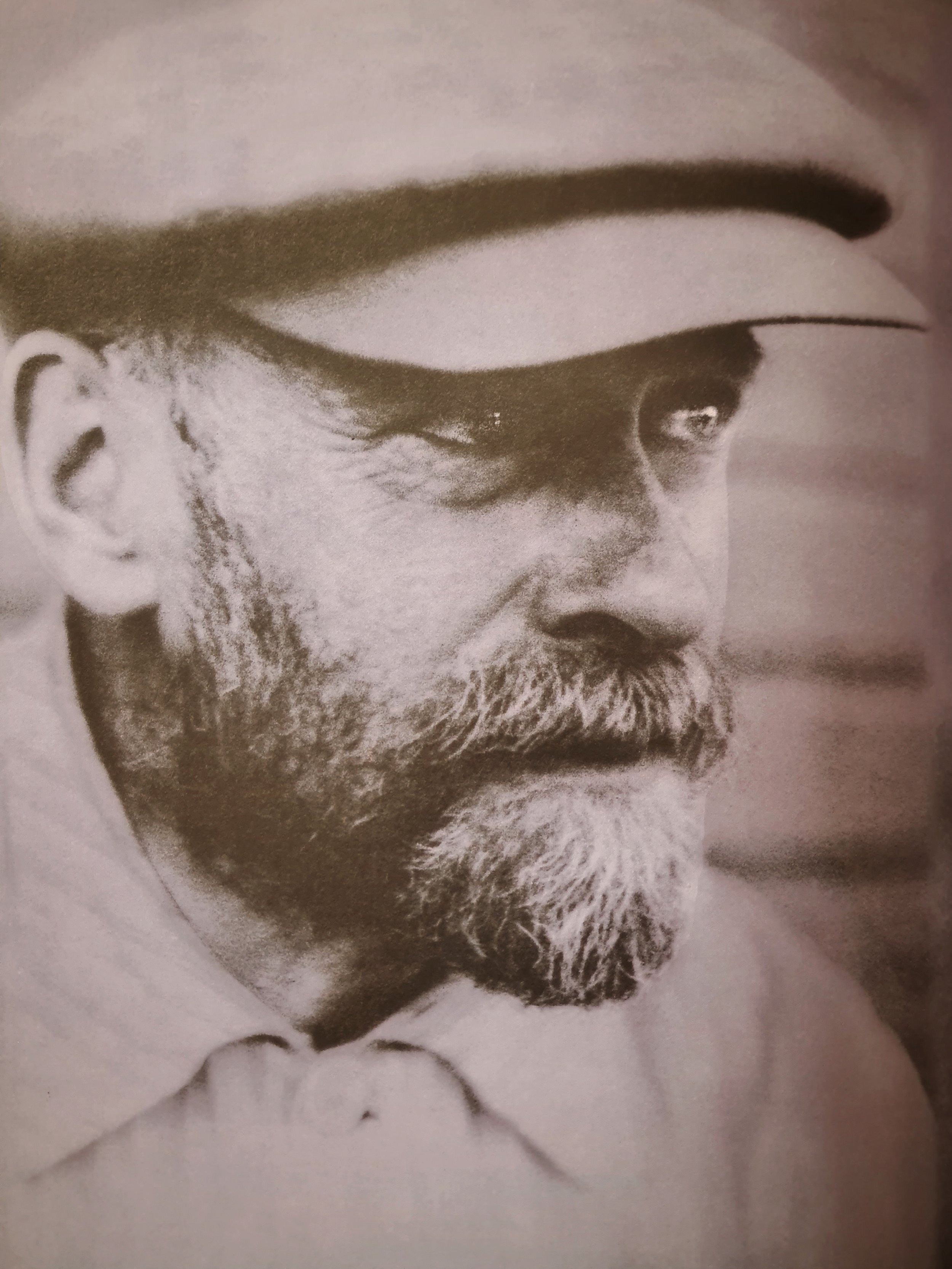

Janusz Korczak.

A very brief history of the father of children's rights.

Janusz Korczak. A supposedly well-known man... When I have studied in Ireland, no one knew the name except people whose studies or interests revolved around children's rights. Even in Poland, he is generally associated as a martyr, a man who sacrificed his life to accompany children on the road to certain death, despite repeatedly being offered help to get out of the Warsaw Ghetto during the Second World War. But Janusz Korczak left a legacy; too little is known and spoken about him. A legacy of children's rights-not only on paper, but also in practice. So who was this man?

Origins

Janusz Korczak is just a literary name for Henryk Goldszmit, who, in addition to his literary talent, was also involved in medicine, social work, management, fundraising, volunteering and pedagogy. His father was born in Hrubieszów, just across the border from Ukraine, to a progressive Jewish family. In those days it was not easy for people of that religion, repressed and discriminated against. On the one hand, Jewish circles were accused of closing themselves off from the outside world; on the other hand, it was made difficult for them to function in it. Only the most outstanding were able to get into university and make a career. Korczak's grandfather began his medical studies at the age of 30 and, according to sources, ran a surgical practice in Hrubieszów.

Olczak-Ronikier writes: It was an ideal, as it seems, family. Loving parents, five or six children, prosperity, warmth, a sense of security. They tried to combine tradition with progress, and Jewishness with Polishness. The precepts and prohibitions of Judaism were respected, religious holidays were celebrated solemnly, but the outside world and its demands were not closed off. Sons were sent to secular schools, it was known that boys had to graduate from higher education to become intellectuals, and girls would marry educated Jews (30-31, 2011). Korczak's father, Józef Goldszmit, grew up and was educated at a time when Poland, occupied by three partitioning powers, was racked by revolutionary uprisings aimed at gaining independence. Thousands of people were being executed, sent with their families to Siberia, estates confiscated, and the use of the Polish language forbidden. In this atmosphere, Józef Goldszmit graduated from grammar school, and went on to study law and administration in Warsaw. He became a respected lawyer there, to whom first a daughter, Anna, and then a son were born. The parents had difficulties in naming their son; on the one hand, they wanted to preserve tradition and give him a Jewish name, while on the other hand, a Polish name was also important to them, so that their son would not be alienated in society. To date, it is not known whether he was born in 1878 or 1879, because his father delayed for a long time in registering his birth. In an act of compromise between tradition and fitting in with society, he was given the name Hersh, and was called Henryk.

Growing up

Did he have a happy childhood? He grew up in a well-off family, but was troubled by loneliness. Very attached to his grandmother, he quietly watched his parents' failed marriage. His strict, domineering father was rarely seen at home, his mother was unhappy and tried to appease her husband. Janusz Korczak was an exemplary student and began writing and publishing his works in magazines as early as middle school. As time passed, they became more and more popular, columns, articles published in popular magazines, but also books or plays. When his grandmother died and his father was getting more and more aggressive attacks, Korczak started tutoring to help the family financially.

The father’s help kept deteriorating. After one of his more severe attacks, Józef Goldszmit was placed in a psychiatric hospital and died not long afterwards at the age of 50. It is believed that he contracted syphilis, an incurable disease at the time and believed to be hereditary. This fact is believed to have weighed on many decisions in Korczak's private life, fearing the disease later in his life.

*Syphilis causes impaired physical and mental function, attacks of insanity, following brain and spinal cord lesions and dementia.

Youth

Korczak's writing and publishing got him into medical school and he discovered the charms of Warsaw. On the recommendation of a doctor he was acquainted with, in 1904 Korczak went as a guardian on holiday with a group of children of Jewish origin. It was probably then that he first encountered his pedagogical vocation. At the summer camp, Korczak was already frequently accompanying children who, growing up in the squalor of the Warsaw gutter, were able to experience the charms of the countryside and nature.

In the tumultuous year of 1905, the Workers were often on strike. They demanded better working conditions and freedom of speech, while students demanded the return of Polish as the language of instruction. Despite the boycott of the universities and their closure, Korczak managed to pass his exams and became a doctor.

He briefly worked at a hospital before being called up for the last months of the Russo-Japanese War. He worked as a doctor, bringing aid to the severely wounded at various points.

Adulthood

He returned to Warsaw in 1906 and to his position at the hospital. He treated both the poor and the wealthy, especially children. Often refused to be paid, he was known in literary circles, but also among the radical socialist and communist intellectuals. He acquired a growing fame among his readers. Goldszmit went away every year as guardian to summer camps and could not decide on what to concentrate his attention on; he hesitated between pedagogy and medicine. As part of his further education, he spent a few months in Paris and London. He even lived in Berlin for a year. Back in Warsaw, going with the flow of favourable initiative, supported by donations, Korczak set about building a home for orphans, to which he also planned to move. His plan was supported by Stefania Wilczyńska, a close and long-time co-worker.

Orphans' Home

The Orphans' Home was opened on 27 February 1913. Korczak was 35 years old at the time. The home could accommodate around 100 pupils up to the age of 13. It is hard to imagine the extent of the poverty the children came from. In the poorest districts, whole, large families lived in one-room flats without sewage systems. The guttering in the street served as the sewerage system. During a storm or downpour, water would mix with the waste and sometimes pour into the flats. Instead of flooring, it was not uncommon for flats to be covered with sand, in which vermin would breed. Rats were also a normal occurrence. Not surprisingly there was a long queue of applicants for each place in the Orphanage. The House of Orphans was not only a rescue from poverty, but also a chance for a better future, despite the resentment of many Poles towards Jews. The House's innovative concept of self-management and liberal methods of working with children aroused great interest.

Olczak-Ronikier writes that Korczak's pedagogical experiments are based on the philosophy of the freemasons, whose lodge Korczak also belonged to. It is not difficult to imagine that an attempt to define children's rights and to respect them could come from tolerance towards diverse human nature, the idea of working on oneself and helping other people.

In August 1914, the First World War broke out and Goldschmit went to the front again to help the wounded. He spent the war mainly in Polesia and Volhynia (the area of today's Ukraine). There, there was fighting between Russian and German-Austrian forces. Stefania Wilczyńska was left alone to guard the Orphans' Home. Goldschmit returned in 1918. In the meantime, he also visited orphanages in Kiev during his leave and met Maria Falska, his later collaborator, there. When Korczak returned to Warsaw, the House of Orphans had gone through a deadly wave of typhus and the streets of the capital were in chaos. Provisions were hard to come by in those days and Polish-Jewish relations were deteriorating. Anti-Semitic reprisals were occurring with increasing frequency. Maria Falska took on the management of a new home for orphans in Pruszków, whose programme was modelled on Korczak's theories and programme. There was never enough money; numerous donation campaigns could not help enough. In Poland (but also in the whole of Europe) dangerous and contagious infections raged, such as Spanish flu, dysentery, but also typhoid fever, which Korczak also contracted.

The unconscious son was cared for by his mother, who unfortunately also became infected and died. In the same year Korczak moved into the Orphans' Home, liquidating his mother's flat. In 1922 Korczak joined the newly opened State Institute of Special Pedagogy. He did not stop writing, creating and publishing and became the editor of a magazine for children and young people.

A dormitory/boarding school was opened at the House of Orphans, where pupils who had already reached the age of 13, but also outsiders studying pedagogy, could learn about the Korczakian system. The main task of the trainees was to record their observations and their own thoughts. Korczak required them to be conscientious, disciplined and constantly reflecting on themselves. Waking up hour was at 6am, followed by meals with the children. Return to the Home was always set at 10 p.m., on Saturdays at 11 p.m. Despite their excellent training, it was difficult for the pupils to find work. Rarely Jews were employed in public jobs.

Korczak was also criticised. Olczak-Ronikier writes: He was attacked by everyone. Traditional Jews about him polonising children, Poles and assimilated Jews about him unnecessarily perpetuating a sense of Jewish identity in his pupils, making integration into Polish society difficult. Zionists, because he did not agitate for an exodus to Palestine. Communists, because he did not call for a fight against capitalism (278, 2011). Despite this, Korczak continued to work. In the early 1930s, he even decided to make two trips to Palestine. Letters written by him indicate his deteriorating wellbeing, perhaps even the seeds of depression, from which he saved himself by prolonged stays in the countryside. In 1938 he hosted a radio programme for adults. He managed to relax again at a summer resort with children before war broke out.

Ghetto

The war began on 1 September 1939. For a whole month Warsaw defended itself, supported by the army and the civilian population. Constant bombardment, shelling, burning buildings, tens of thousands of wounded, lack of food, medical supplies, communication meant that the capital had to surrender. The Polish army left the city, replaced by the German army. Korczak made himself an officer's uniform, which he wore every day. He did not comply with the order to wear an armband with a Star of David.

In 1940, the Nazis were catching people in the streets en masse, arresting them and deporting them. There was a shortage of food, especially fats-milk or butter was unavailable. Food rations for the Jewish population were drastically reduced. They began to build walls to create a ghetto. Despite the bans and the horror, the Doctor managed to organise the last summer camps for children from the Orphanage and other orphanages.

In October 1940, all Jews were ordered to move to the ghetto. They were allowed to take only small luggage and bedding. Korczak, through his connections, managed to secure a building for the orphans. During the move, the Doctor defied German soldiers stealing rations from the people being moved. He was publicly slapped, arrested and taken to the Pawiak prison (a place were interrogations and torture took place). He got out thanks to bail posted by two wealthy Jewish collaborators (the were collaborating with Nazis). The small district (the boundaries of which were further reduced over time), could accommodate around 100,000 people. Some 500,000 were squeezed into it, and more residents were arriving all the time, sent to the ghetto from the surrounding villages and towns. The Doctor was repeatedly offered help to get out of the ghetto. He refused each time.

Korczak and the other educators did their best to keep the life of the pupils going as usual. Time was filled tightly with activities. No room was left for fear. The pre-war rules and daily schedule were in force. The children studied, took care of cleanliness and order, helped in the kitchen and in the sewing room, the older ones looked after the younger ones (Olczak-Ronikier, 373, 2011). In addition to celebrating Jewish holidays, readings, concerts and storytelling were held at the orphanage.

Despite the fact that Korczak's health was declining more and more, he decided to take up a job at the Main Shelter House in the Ghetto, to which abandoned children found on the street were taken. The conditions were terrible: Unheated rooms. No light. No fuel. No clothing. A curtain converted into nappies, cloth from a conference table into two blankets, national flags into blouses. Lack of medicines. Frostbite, sores. Diarrhoea. Coccus. Scabies. Above all, hunger (Olczak-Ronikier, 389, 2011). Patients exhausted, starving to death. Which child to save? Which one to leave to die? Every doctor in the ghetto had to make such decisions every day.

In July 1942, the systematic deportation of ghetto inhabitants to the Treblinka gas chambers began. Every day, 7,000 people were transported, chased out of their homes. In the first days of August, the House of Orphans too was escorted to freight wagons. The same motifs recur in many accounts: the punitive, proud march through the ghetto. In fives. In other versions-sixes. The festive clothes of the children. Smiling faces. A green banner flying above the march (Olczak-Ronikier, 437, 2011). Reportedly, and at the last moment, efforts were made to save Korczak, who would have had to leave the children behind. Fulfilling his duty as an educator and doctor bringing help to others, he became a hero.

His extensive work about children served as a fundament when creating the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Until today his innovative methods continue to inspire and motivate.

Sources:

Olczak-Ronikier, Joanna (2011) Korczak. Próba Biografii. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo W.A.B

Markowska-Manista, U., (2020) Korczak, Janusz. In Cook, D. (ed) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood Studies, Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Markowska-Manista, U., Zakrzewska-Olędzka, D. (2020) Children’s Rights Through Janusz Korczak’s Perspective and Their Relation To Children’s Social Participation. In In: Thomas S., Hildebrandt F., Rothmaler J., Pigorsch S., Budde R. (Eds.) Partizipation in der Bildungsforschung. Weinheim und Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Sadowski, Maciej (2012) Janusz Korczak. Fotobiografia. Warszawa: Iskry (Fotos)